For what it’s worth, Wendell Berry gets a good deal of the blame and/or thanks for my move, from New York City to my wife’s family farm in central Kentucky, and for my haphazard Adventures in Farming.

For some time, I wrote a blog inspired in part by a poem of his.

So far my actual agrarian experience has not exactly resembled that enjoyed by Berry on his Henry County farm. I am not using draft horses, and, in spite of my best efforts, am surely not making the wisest use of the land and resources at my disposal. Nor am I writing with pencil and 1957 vintage Royal typewriter. My household has not one, but four computers, as well as four vehicles, all with between 140,000 and 210,000 miles on the odometer.

In darker moments, I think my rustic idyll seems more akin to that of the fictional farmer Jean de Florette, an eager, idealistic city-slicker accountant who moves to Provence from Paris, and is driven to madness, to bankruptcy, to death, by unkind weather and scheming provincials. (At this point, I am only partway to madness. Bankruptcy and death still seem to be a good way in the distance.)

Still, Berry’s ideas and attitude loom large over many of my daily actions. Sometimes I feel I should have a wristband engraved with the letters, WWWD (What Would Wendell Do?).

I came face to face with him at a Kentucky Book Fair a few years back. He signed the book I had asked him to sign, and looked up with expectation of conversation of some sort, but all I could conjure was a Ralph Kramden-esque “hummana hummana”.

It has dawned on my in recent months that I am not him, and can never be. There are some, many of his ideas and practices that I strive to adopt, but he has set the bar at a great height. I try as much as I can to be sustainable and conscious in everything I do, but realize that most of the time I fall far short. I realize he might tut-tut the fact that I like to play golf, have 6,000 songs in my ITunes, quaff a 30-pack of Old Style every week, subscribe to women’s fashion magazines. I am pretty sure he would not find much to be amused by in Zoolander or Caddyshack.

Having gotten all that out of the way, I would submit, without fear of overstatement, that he would get my vote for the Greatest Kentuckian Living (well back in the distance: a boxer from Louisville, and a girl singer from Butcher Holler). His poetry can be absolutely transcendent. (start here for a sampling); his fictional world a rival to that of Faulkner for completeness and depth; and his essays are at once uplifting and, as I have hinted here, impossibly challenging.

He will be speaking in several venues in Danville for the entire day, which is pretty thrilling to me. If child care obligations can be rearranged, I am hoping to see him at least once, if not twice.

In preparing for his visit, I have been re-reading some of his essays, and have come across some things I had not seen.

I particularly enjoyed his “Why I am NOT going to buy a computer” from 1987, which comes complete with a series of passionate reactions from readers of Harper‘s magazine, where it was reprinted in the late 80s. Berry’s answers to those reactions, also included, show the man at his most crotchety (to me, a good thing) and most caustic.

Through the genius of hypertext (an innovation Berry finds close to hilarious), that essay links to “The joy of sales resistance”, featuring one of his most contrarian, unpopular (and spot-on) ideas, that education has been turned into just another commodity.

This is another highly acerbic essay, one in which Multiculturalism, the Free Market, and Unlimited Economic Growth come in for a mauling. Though written in the early nineties, it contains what would be a great manifesto for the modern conservative movement, and a large segment of the Democratic Party (although it would surely not be recognized as satire):

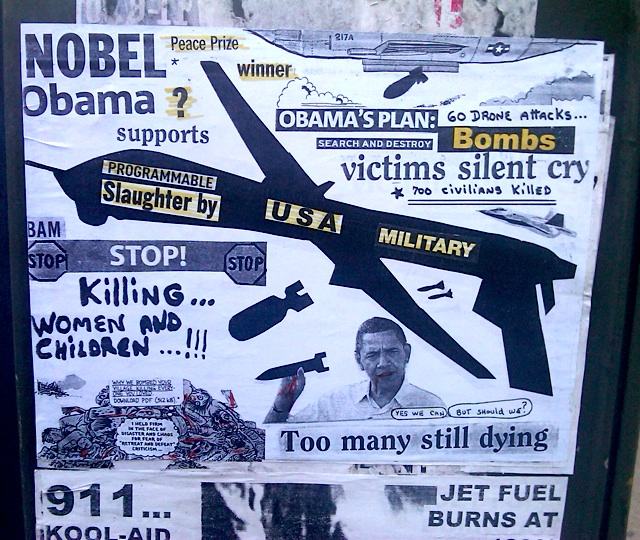

Reduce the Government. The government should only be big enough to annihilate any country and (if necessary) every country, to spy on its citizens and on other governments, to keep big secrets, and to see to the health and happiness of large corporations. A government thus reduced will be almost too small to notice and will require almost no taxes and spend almost no money.

Looking for an arbitrary way to wind up this drifting meditation, here, without further comment, a poem from A Timbered Choir—The Sabbath Poems 1979-1997:

The year begins with war.

Our bombs fall day and night,

Hour after hour, by death

Abroad appeasing wrath,

Folly, and greed at home.

Upon our giddy tower

We’d oversway the world.

Our hate comes down to kill

Those whom we do not see,

For we have given up

Our sight to those in power

And to machines, and now

Are blind to all the world.

This is a nation where

No lovely thing can last.

We trample, gouge, and blast;

The people leave the land;

The land flows to the sea.

Fine men and women die,

The fine old houses fall,

The fine old trees come down:

Highway and shopping mall

Still guarantee the right

And liberty to be

A peaceful murderer,

A murderous worshipper,

A slender glutton, Forgiving

No enemy, forgiven

By none, we live the death

Of liberty, become

What we have feared to be.