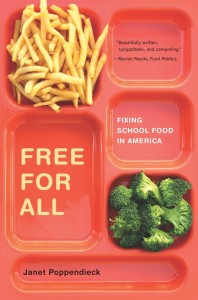

“It will take 2 million angry moms to change school food,” says Susan Coombs, former Texas Agriculture Secretary, who is quoted in Janet Poppendieck’s Free for All: Fixing School Food in America.

“It will take 2 million angry moms to change school food,” says Susan Coombs, former Texas Agriculture Secretary, who is quoted in Janet Poppendieck’s Free for All: Fixing School Food in America.

I’ve only just read a review of the book, and want this dad’s name added to the list of angry moms.

This happens to be a week I am also digesting a full-hour interview with Michael Pollan on Democracy Now, as well as my third viewing of Food Inc., which is the best single document to introduce the unaware into the batshit crazy place that is America’s food system.

It’s a convoluted contraption, with a few big winners and lots and lots of losers.

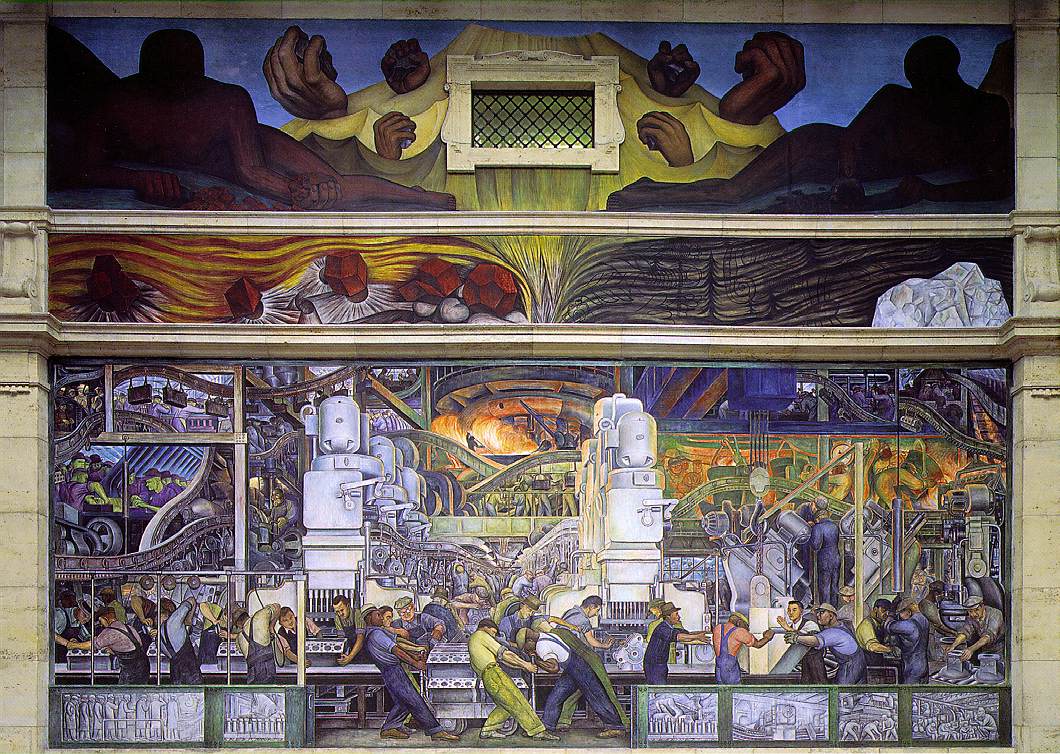

Those profiting (mightily) from our national food dysfunction include executives and shareholders of the various Big Ag corporations–Monsanto, ConAgra, ADM, Cargill, Smithfield, Tyson, Perdue– and the large farms that receive the bulk of subsidy payments for growing massive surpluses of corn and soybeans.

The losers are just about everyone else. The victims who suffer the most include small farmers; the abused cattle, pigs, and chickens who are treated like mechanical cogs, not living beings; the horribly stressed and underpaid factory farm workers who are treated only marginally better than the animals; and … and … our children, who, via the school lunch program, are the last stop for the last bits of that surplus production that no one else wants. Pollan calls it “a dispose-all system for surplus agricultural commodities.”

Here is a summary of the problem, and Poppendieck’s proposed radical solution, via Mark Winne on Civil Eats:

Why, for instance, have we developed three different ways to pay the lunch lady–one for the poor students, one for the nearly poor, and one for those who supposedly are being driven in BMWs to school? The logical answer might be because that’s fair; the rich kids should pay more and the government should subsidize the cost of feeding lower income children, as it does currently to the tune of $11 billion annually. But as Poppendieck peels back the layers of the onion, we find the issue has always been less about compassion for needy children and more about accommodating political and commercial interests. Harry Truman (school lunch is good for national security), Ronald Reagan (ketchup is a vegetable), nutritionists and nutritionism (its nutrients that count, not the quality and taste of food), and various agricultural lobbies wanting to unload their farm surpluses are just a sampling of what has driven the school food agenda. Somewhere low on the totem pole you’ll find concern for the health and well-being of boys and girls.

…

Poppendieck’s jargon-free narrative takes us step-by-step through the deals, concessions, and compromises that have bureaucratized the school food process while simultaneously dumbing down the food. Why is so much processed food used to prepare school meals? Because it’s cheaper and “cooking from scratch” kitchens have been removed from the schools. Why does it have to be cheaper when we’re talking about feeding our children? Because the federal government (or anyone else for that matter) will not provide enough funding to enable schools to buy fresh, whole ingredients. (And by the way, taxpayers are spending billions of dollars to subsidize corn and soybeans, the prime ingredients in processed food.) Why do we have so many junk food items sold “a la carte” in our schools? Well, in addition to using a French culinary phrase to disguise what is otherwise crappy food, schools must sell these items to those with discretionary cash–supposedly the ones in the BMWs–to compensate for the low reimbursements they receive for meals that meet mandated USDA standards. And on it goes.

Poppendieck has a solution that is as elegant as it will be hard to achieve–universal free meals for all students K through 12. She acknowledges the cost, an additional $12 billion per year (our present wars, please note, are costing about the same amount each month) that would not only feed all students for free, but also improve the quality of the food.

If the arguments for universal school meals–efficiency, equity, no one excluded–sound eerily familiar, then you’ve probably been paying attention to the arguments for universal health care. If nothing else, it’s certainly ironic to consider the consequences of removing each system’s respective middlemen: processed food purveyors for school food, and private health insurers for health care. Might we all be healthier as a result?

This food and kids thing is a big battle in our house. I work hard to have good food around: we raise our own meat and veggies (in season), but we’re always battling peer pressure, fast food and (this one really kills me) all the free toys the kids get when they eat fast food.

In spite of all my efforts, my kids ingest more than their fair share of sugary cereal, pizza, and chicken nuggets– both at school and (sadly) at home. I have to weigh the risk of alienating them from good food altogether (if I push too hard) against the ill effects of the crap they prefer. It ain’t easy. I like to hope that the exposure to real food will at some future point mutate into a desire to eat it, but I can’t be sure.

I’m not exactly optimistic that Congress and the White House will find the $12 billion to give free, nutritious school lunches for all of our kids. That’s putting it mildly. It’s not going to happen with the current crew. But we have to start demanding it.